Composition

Atoms consist of a nucleus of protons ( \({}^1_1p\) ) and neutrons ( \({}^1_0n\) ), called nucleons, together with surrounding electrons ( \({}^{\ \ \ 0}_{-1}e\) ).

Notation: \({}^A_Z X^C\)

- \(X\) the element symbol

- \(Z\) the atomic number (the number of protons)

- \(A = Z + N\) the mass number (with \(N\) the number of neutrons)

- \(C\) the overall charge of the atom

Elements are determined by their number of protons.

A neutral atom has the same number of protons and electrons, thus has an overall net charge of 0.

- \({}^1_1H\) is a neutral Hydrogen atom consisting of 1 proton and 1 electron.

- \({}^4_2He\) is a Helium atom with 2 protons, 2 neutrons, and 2 electrons.

An ion has a different number of electrons, and thus has a positive or negative net charge. Ionizing radiation is anything that has enough energy to eject an electron from an atom, thus forming an ion.

- \({}^4_2He^{+}\) is a Helium ion with 2 protons, 2 neutrons, and 3 electrons.

An isotope of an element has a different number of neutrons, and thus has a different mass.

- \({}^2_1H\) is a Hydrogen isotope consisting of 1 proton, 1 neutron, and 1 electron (deuterium).

- \({}^3_1H\) is a Hydrogen isotope consisting of 1 proton, 2 neutrons, and 1 electron (tritium).

Nucleus

Nuclei are quantum mechanical systems, thus can be found in different energy states. \({}^A_Z X\) denotes the ground state, \({}^A_Z X^\ast\) denotes an excited state (with more energy). Long-lived excited states are called isomeric states.

Electrons

Electrons are organized in shells (= energy levels). Each shell can have several subshells in varying orientation. These oriented subshells are call orbitals, and each orbital can hold two electrons.

| subshell | orbitals | max. electrons |

|---|---|---|

| s | 1 | 2 |

| p | 3 | 6 |

| d | 5 | 10 |

| f | 7 | 14 |

Here is the orbitals a shell can have:

| shell | orbitals | max. orbitals | max. electrons |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1n | 1s | 1 (1 s) | 2 |

| 2n | 2s 2p | 4 (1 s + 3 p) | 8 |

| 3n | 3s 3p 3d | 9 (1 s + 3 p + 5 d) | 18 |

| 4n | 4s 4p 4d 4f | 16 (1 s + 3 p + 5 d + 7 f) | 32 |

Atoms tend towards their lowest energy state, so electrons first fill the innermost shell. For filling order, cf. the Aufbau principle.

Example electron configurations:

- Hydrogen: \(1s^1\)

- Helium: \(1s^2 = [\text{He}]\)

- Lithium: \([\text{He}]\,2s^1\)

- Carbon: \([\text{He}]\, 2s^2\, 2p^2\)

- Oxygen: \([\text{He}]\, 2s^2\, 2p^4\)

- Neon: \([\text{He}]\, 2s^2\, 2p^6 = [\text{Ne}]\)

- Argon: \([\text{Ne}]\, 3s^2\, 3p^6 = [\text{Ar}]\)

- Calcium: \([\text{Ar}]\, 4s^2\)

Atoms are energetically most stable when they have 8 electrons in the outermost shell (valence electrons), so they strive to form chemical bonds if they have less (donating, accepting, or sharing electrons with other atoms). It is the valence electrons that participate in chemical reactions, so they determine an atom’s reactivity. Inert gases are the group of elements with a fully filled outer shell, so they are not reactive at all.

Electrical charge

Particles with different charge are subject to electrostatic attraction, particles with like charge are subject to electrostatic repulsion.

Most protons p+ have a positive charge, and most electrons e- have a negative charge. (Positive electrons e+ are called positrons and are relatively rare.)

Mass

The atomic weight of an atom is defined as the mass of the neutral atom relative to the mass of a neutral carbon-12 atom (the most common isotope of carbon). Since it is a ratio, it is unitless, specified in terms atomic unit masses amu.

Rest masses of atomic particles:

mass_proton = 1.0072766 amu = 938.256 MeV

mass_neutron = 1.0086654 amu = 939.550 MeV

mass_electron = 0.000548597 amu = 0.511006 MeV

The actual mass of an atom is a bit smaller than the sum of its particles. This mass defect ( \(\Delta = m_\text{atomic} - A\) ) is the atom’s binding energy, see the section below.

Energy

The electrons and nucleons in an atom can be in different states. The ground state is the state of lowest energy and constitutes the one in which the atom is normally found. When an atom possesses more energy than its ground state energy, it is in an excited state.

Atoms do not remain in an excited state indefinitely, they will return to their ground state, usually by emitting a photon.

Mass defect and binding energy

The mass defect ( \(\Delta = m_\text{atomic} - A\) ) is the difference between the sum of the masses of all nucleons (greater) and the observed mass of the nucleus (smaller). This difference corresponds to the binding energy in the nucleus. That is, some of the mass of the nucleons was converted to binding energy when the nucleus was formed, corresponding to the work required in order to separate the nucleons again.

Binding energy:

$$B(A,Z) = (Z\times m_\text{proton} + (A-Z)\times m_\text{neutron} - m_\text{atomic}(A,Z)) c^2 \text{[amu]}$$Using the conversion factor 1 amu = 943.49 \(\frac{\text{MeV}}{c^2} \) , this gives:

$$B(A,Z) = (Z\times m_\text{proton} + (A-Z)\times m_\text{neutron} - m_\text{atomic}(A,Z))\times 943.39 \text{[MeV]}$$Note that binding energy and atomic mass are negatively related, i.e. the higher the binding energy of a nucleus, the lower its mass, and vice versa.

(Also note that \(m_\text{atomic}(A,Z)\) includes the electrons, but the error in disregarding their isolated mass is very small.)

Energy release in nuclear reactions happens on an MeV scale, while chemical reactions release energy on an eV scale. In order to raise the (kinetic) energy of a particle in the MeV range, we thus need particle accelerators (as chemical heating could raise the kinetic energy only in the eV range).

From the right towards iron, fission reactions release binding energy. From the left towards iron, fusion reactions release binding energy.

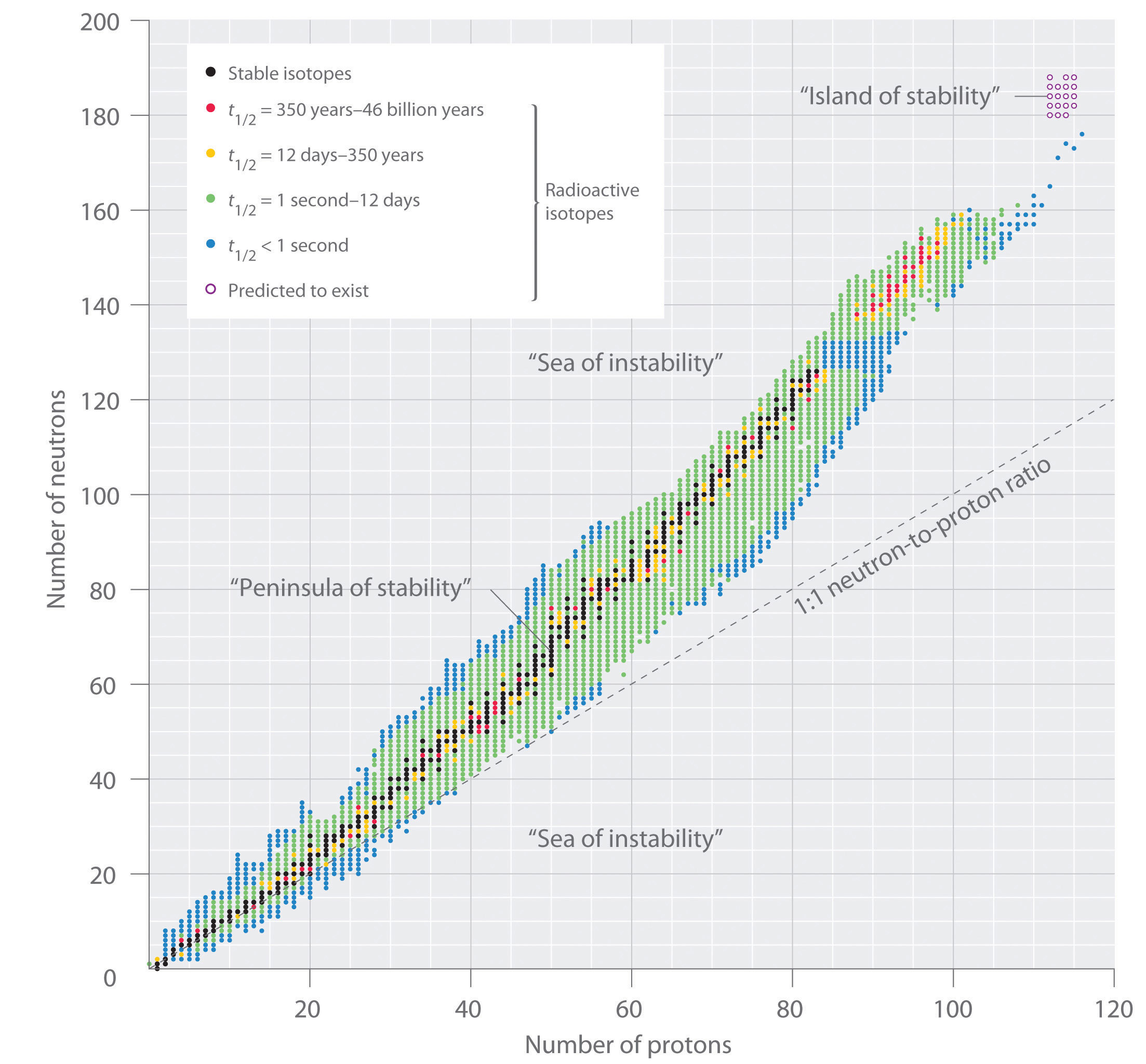

Stability

The stability of a nucleus depends, among others, on the number of nuclei and the ratio of protons vs neutrons, including even vs odd numbers of protons and neutrons. Also, the more binding energy a nucleus has, the more stable it is. (On average, a mass defect \(\Delta > 0\) means the nucleus is stable, while a mass defect \(\Delta < 0\) means the nucleus is unstable.)

Unstable elements decay (usually in a decay chain) in order to reach the most stable configuration.

Elements with \(Z<20\) tend to be stable if \(\frac{N}{Z}=1\) , i.e. if they have the same number of protons and neutrons in the nucleus. With exceptions, e.g. \({}^{14}_{\ 6}C\) (carbon-14) is unstable.

For elements with high \(Z\) , the stable ratio is about \(\frac{N}{Z}=1.5\) , i.e. if they have more neutrons than protons. The reason is that the strong force that holds together protons in the nucleus (overcoming their electrostatic repulsion) acts only at very short distances. In larger nuclei, the distances get too big and finally repulsion begins to win over. More neutrons can help keeping a balance, but only up to a certain point. Elements with \(Z>83\) are pretty much all unstable.

Isotopes with even numbers of protons and neutrons tend to be more stable. Especially stable are nuclei with a magic number of \(Z\) or \(N = 2, 8, 20, 28, 50, 82, 126\) , as the average binding energy per nucleon is higher than expected (maybe because they correspond to closed shells in the nucleus). Also, atoms with a magic number of neutrons are reluctant to absorb neutrons and thus make good materials where neutron absorption must be avoided.

(Image source: Chemistry Libre Texts)