Nuclear reactions are reactions where nuclear particles interact; comprising decay processes as well as collision reactions like fission and fusion.

Notation: \(a + A \to B + b\) or \(A(a,b)B\)

Where:

- \(a\) the projectile

- \(A, B\) nuclei

- \(b\) the ejectile(s)

Nuclear reactions conserve:

- mass (number of nucleons)

- energy

- momentum

- charge

Q-value

The Q-value of a nuclear reaction is a measure of energy transfer: the amount of mass that is turned into energy. Mathematically, it’s the difference between the sum of the masses of the initial reactants and the sum of the masses of the final products.

Given conservation of mass and energy (and the equivalence of mass and energy), for a reaction

$$a + A \to B + b$$the following must hold:

$$E_{a,\text{kin}} + m_a c^2 + E_{A,\text{kin}} + m_A c^2 = E_{B,\text{kin}} + m_B c^2 + E_{b,\text{kin}} m_b c^2$$Sometimes the kinetic energy of a nucleus at rest ( \(E_{A,\text{kin}}\) ) is very small compared to the other kinetic energies, and thus can be neglected. This is, however, not the case for fission with thermal neutrons.

And since the reaction results have equal (though opposite) momentum, we also have:

$$m_b E_{b,\text{kin}} = m_B E_{B,\text{kin}}$$The Q-value is the difference in mass (or kinetic energy) between before and after the reaction:

$$Q=((m_a + m_A) - (m_b + m_B))\,c^2\ \text{[amu]}$$Or, using the conversion factor 1 amu = 943.49 \(\frac{\text{MeV}}{c^2} \) :

$$Q=((m_a + m_A) - (m_b + m_B))\times 931.49\ \text{[MeV]}$$\(m\) can be both the mass of the nuclei and the mass of the neutral atoms (be aware which one, because it does make a difference).

The Q-value can also be computed on the basis of the binding energies:

$$Q=((BE_a + BE_A) - (BE_b + BE_B)) \text{[MeV]}$$(Note that the binding energy of a neutron is 0, as it is not bound anywhere.)

If the binding energy of the product nuclei is larger than that of the initial nucleus, i.e. when the reaction produces a more stable configuration, energy is released.

When \(Q\) is positive, there is a net increase in the energy of the particles. The reaction is exothermic. The energy surplus comes from a conversion of mass to kinetic energy.

When \(Q\) is negative, there is a net decrease in energy, i.e. energy has to be supplied for the reaction to take place. The reaction is endothermic. Energy is usually supplied in the form of kinetic energy of the incident particle, which is then partly converted into mass.

Radioactive decay

Radioactive decay is a special form of nuclear reaction, where a nucleus decays without being hit by an incident particle:

$$A \to B + b$$Emitted particles b are referred to by their Greek letters when they come from the nucleus. So its origin from the nucleus is what what makes Helium an alpha particle, what makes an electron or positron a beta particle, and what makes photons gamma rays.

From the conservation of momentum and mass/energy, we can determine the kinetic energy of b:

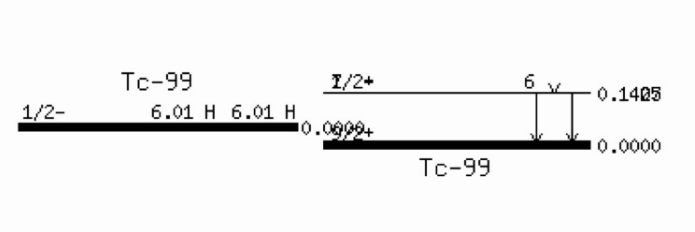

$$E_{b,\text{kin}} = Q \frac{m_B}{m_b + m_B}$$Decay diagrams:

- The y-axis plots energy, i.e. arrows down mean energy is released. Energy here means energy relative to the ground state of the daughter nucleus (not absolute energy).

- The x-axis is atomic number Z, i.e. an arrow to the left means decreasing the number of protons, an arrow to the right means increasing the number of protons, and a straight line down means the atomic number does not change.

Alpha decay

$${}^A_Z X \to {}^{A-4}_{Z-2} Y^{(-2)} + {}^4_2He^{(+2)}$$A relatively heavy atom emits an alpha particle, in order to get to a more stable state. Alpha particles are Helium nuclei \({}^4_2He^{2+}\) , i.e. Helium atoms stripped off their electrons. The positive charge of \(+2\) , in fact, doesn’t last long, as alpha particles are very quick to grab two electrons; likewise \(Y\) has a negative charge of \(-2\) but very quickly loses the two excess electrons.

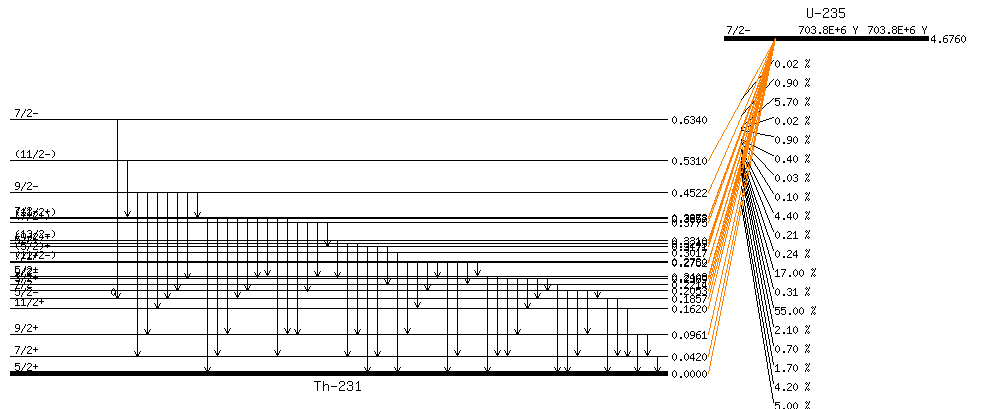

Example:

Beta decay

Beta decay comes in two flavors, with beta particles being electrons and positrons from the nucleus.

Beta minus ( \(\beta^-\) ) decay

$${}^A_Z X \to {}^{\ \ \ \ A}_{Z+1} Y^{(+)} + {}^0_0e^{-1} + {}^0_0\overline{v}$$A nucleus emits an electron and an antineutrino, thus converting a neutron into a proton. This is one way of an unstable nucleus with too many neutrons to become more stable.

The resulting atom \(Y\) has a positive charge but is very quick in capturing an electron to become neutral again.

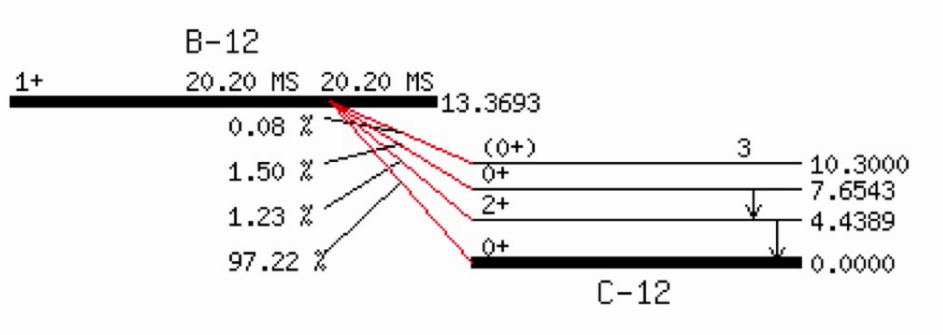

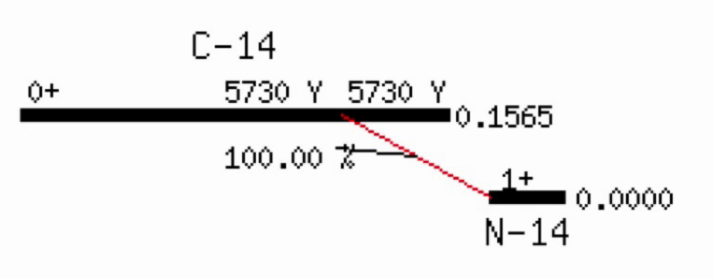

Example:

Beta plus ( \(\beta^+\) ) decay

$${}^A_Z X \to {}^{\ \ \ \ A}_{Z-1} Y^{-1} + {}^0_0e^{+1} + {}^0_0v$$A nucleus emits a positron and a neutrino, thus converting a proton into a neutron. This is one way of an unstable nucleus with too many protons to become more stable.

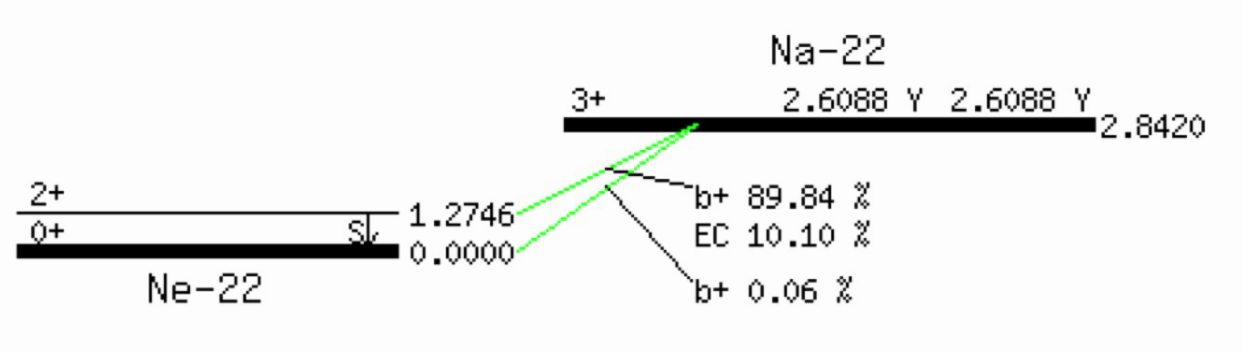

Example (EC = electron capture):

Electron capture

$${}^A_Z X \to {}^{\ \ \ \ A}_{Z-1} Y$$A competing process to beta minus decay is electron capture (EC), where the nucleus captures an inner shell electron, thus reducing the nuclear charge by 1. (The overall charge of the atom does not change, but it is now in an excited state because of the vacancy in one of its inner shells.)

Neutron emission

$${}^A_Z X \to {}^{A-1}_{\ \ \ \ Z} Y + {}^1_0n$$This happens for exceptionally unstable nuclei.

Gamma decay

$${}^A_Z X^\ast \to {}^A_Z X + {}^0_0\gamma$$Reconfiguration of an atom to go from an excited state to a ground state. (Often follows beta decay, which rarely takes the nucleus to a ground state.) The nucleus is not changing, it just loses energy but emitting high energy gamma rays \({}^0_0\gamma\) . These high wave-length electromagnetic waves are photons, particles with zero rest mass and charge, traveling at the speed of light.

Usually, the de-excitement happens in an unmeasurable short time after the excited state was formed. When it is delayed, the longer-lived excited states are called isomeric states, and decays from these states are called isomeric transitions (IT).

Example:

IT competes with with internal conversion (IC), which can be thought of the gamma ray hitting an electron on the way out of the nucleus, leading to the gamma ray to be absorbed and the electron to be emitted from the atom. Subsequently, an outer electron will fill the resulting hole, emitting an x-ray (which could also be thought of as hitting an electron on the way out; the thus emitted electron, usually from an outer shell, is called Auger electron).

Spontaneous fission

Emission of neutrons.

Happens with very heavy (and unstable) elements, but usually with very low probability.

Activity and decay rate

The activity \(A\) [ \(\frac{\text{decays}}{cm^3 s}\) ] is defined as \(A=\lambda N\) , where \(N\) is the number of nuclei present per volume [ \(\frac{\text{atoms}}{cm^3}\) ], and \(\lambda\) is the decay constant for the element [ \(s^{-1}\) ].

Not regarding volume, \(N\) is simply the number of nuclei present and \(A\) is in \(\frac{\text{decays}}{s}\) , which is named Bq (or Ci for more manageable numbers).

The decay rate of a nucleus is specified as:

$$\frac{dN}{dt}=-\lambda N$$If nuclides are also produced at a constant rate \(R\) , the right-hand side changes to \(-\lambda N + R\) . The analytical solution to the above differential equation is:

$$N(t)=N(0)\,e^{-\lambda t}$$Where \(N(t)\) is the number of nuclei still present at time \(t\) , and \(N(0)\) is the initial number of nuclei. Or, in the case of simultaneous constant production:

$$N(t)=N(0)\,e^{-\lambda (t)} + \frac{R}{\lambda}(1-e^{-\lambda (t)})$$\(\frac{N(t)}{N(0)}\) is the ratio of nuclei surviving until time \(t\) . This can be seen as the probability of one nucleus to survive up to \(t\) , so \(1-\frac{N(t)}{N(0)}\) corresponds to the probability of the nucleus decaying until \(t\) . With \(\frac{N(t)}{N(0)}=e^{-\lambda t}\) ", this gives the following probability of a nucleus to have decayed after time \(t\) :

$$p = 1 - e^{-\lambda t}$$(For infinitesimal \(t\) this can be approximated as \(\lambda t\) .)

This matches the intuition that the probability of decaying until one half-life is 0.5, the probability of decaying until two half-lives is 0.75 (0.5 + 0.5*0.5, or: the conditional probability of decaying within one half-life plus the conditional probability of decaying within the second half-life given it survived the first half-life), and the probability of decaying within a very large number of half-lives approaches 1.

The decay constant is related to the half-life \(T\) as follows (which we arrive at when setting \(N=\frac{1}{2}N(0)\) "):

$$\lambda = \cfrac{\text{ln}\,2}{T}$$ and \(T = \cfrac{\text{ln}\,2}{\lambda}\)

The average life expectancy (or mean life) of a nucleus is \(\frac{1}{\lambda}\) .

Generally, the larger an element’s decay constant \(\lambda\) , the faster its decay and the shorter its half-life.

Code: github.com/cunger/simulacron/nuclei

Radioactive dating

Solving the decay equation for \(t\) allows for radioactive dating, e.g. where \(N(t)\) is the current amount of carbon-14 present in the sample, \(N(0)\) is the amount of carbon-14 in living tissue, and the half life of carbon-14 is 5700 years.

Code: decay.exs

Serial radioactive decay

In general, change = production - destruction. So for a linear decay chain:

$$N_1 \xrightarrow{\lambda_1} N_2 \xrightarrow{\lambda_2} N3$$We have the following set of differential equations:

- \(\cfrac{dN_1}{dt}=0 - \lambda_1 N_1\)

- \(\cfrac{dN_2}{dt}=\lambda_1 N_1 - \lambda_2 N_2\)

- \(\cfrac{dN_3}{dt}=\lambda_2 N_2 - 0\)

(The general form is referred to as Bateman equations.)

If there is also other nuclear reactions involved, they can be added as additional terms for production and destruction, e.g. by including the reaction rate \(\sigma \Phi N_i\) , where \(\sigma\) is the cross-section [ \(cm^2\) ] and \(\Phi\) is the neutron flux [ \(\frac{\text{neutrons}}{cm^2 s}\) ].