Neutrons have roughly the same mass as a proton, but no charge.

Neutrons have a larger range than charged particles, because they don’t interact with the electrons in the atoms of matter, as they have no charge.

Free neutrons

Free neutrons are unstable, with a halflife of about 10.4 minutes. They undergo \(\beta^-\) decay, yielding a proton, an electron and an antineutrino: $${}^1_0n \to {}^1_1p + {}^{\ \ \,0}_{-1}e + \overline{v}$$

Classification

Free neutrons can be classified according to their kinetic energy. They can be roughly divided into three energy ranges:

- Thermal neutrons (up to 1 eV) are in a thermal equilibrium with their surrounding, with the most probable energy at 20 degrees C being 0.025 eV (~ 2km/s). They often have a much larger neutron absorption cross-section than fast neutrons.

- Resonance neutrons (1 eV - 100 keV) have energies where the neutron capture cross-sections peak, and the probability of capture exceeds the probability of fusion.

- Fast neutrons (1-10 MeV) are produced by nuclear fission. They have a Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution of energy with a mean energy of 2 MeV in the case of uranium-235 fission.

Thermal reactors use thermal neutrons to sustain the fission chain reaction. They thus slow down the produced fast neutrons using a neutron moderator, until their energy is in thermal equilibrium with the atoms in the system. Fast reactors, on the other hand, use fast neutrons to sustain the fission chain reaction, not using any neutron moderator.

The energy of a neutron has a big impact on its cross-sections. An important property of a reactor core thus is its neutron energy distribution.

Neutron interactions

Since neutrons have no charge, they pass easily through electron clouds and directly interact with nuclei. Those interactions can be thought of as two steps: first the neutron is absorbed by the nucleus, forming a compound nucleus, which then decays.

There are two main kinds of interactions: scattering and absorption.

Elastic scattering (n,n): The neutron and nucleus are left unchanged, no energy is transferred. That is, Q=0. It can be understood as a collision where the neutron bounces off the nucleus, and is the only interaction that is not considered to form a compound nucleus.

Inelastic scattering (n,n'): The neutron penetrates the nucleus, forming a compound nucleus in an excited state. This compound nucleus returns to its ground state by gamma decay, emitting a neutron (on a different energy level than the incoming one, so energy was transferred).

In general, scattering refers to nuclear reactions in which the outgoing particle is the same as the incident particle.

Radioactive capture (n, \(\gamma\) ): The neutron is absorbed by the nucleus, and gamma rays are emitted. Other neutron absorption reactions are (n, \(\alpha\) ) and (n,p), which can be either exothermic or endothermic.

Neutron production (n,2n) and (n,3n): The nucleus emits one or more neutrons. For example, \({}^2H\) and \({}^9Be\) have loosely bound neutrons that can easily be extracted.

Fission: The neutron causes the nucleus to split into two fission products, emitting 2 to 4 neutrons and releasing energy. $$X \to Y + Z + {}^1_0n$$ This can also happen spontaneously, but its probability is low. (Californium has an exceedingly high probability for spontaneous fission, ~3%, which is why it is sometimes used to jumpstart nuclear reactors).

Example: Uranium fission

$${}^1_0n + {}^{235}_{92}U \,\to\, {}^{236}_{92}U \,\to\, {}^{92}_{36}Kr + {}^{141}_{56}Ba + 2.44{}^1_0n$$The energy of the resulting neutrons is a probability distribution, with the most likely energy ~700 keV and the average energy ~2 MeV. The are, however, too high-energy to engage in further fission events. In a reactor, they thus need to be slowed down by a moderator like water, where neutrons successively lose energy through elastic scattering.

Cross-sections

Cross-sections characterize the probability of a neutron interaction, quantified in terms of characteristic target areas (where a larger area means a larger probability of interaction).

The microscopic cross-section \(\sigma\) specifies the probability of a particular neutron interaction with a target nucleus. It depends on the target nucleus, the type of reaction, the neutron energy, and the target energy.

The macroscopic cross-section \(\Sigma\) specifies this probability of a neutron interaction for the whole medium. It is considered per unit path length that the neutron travels. The average distance a neutron travels before interacting with a nucleus is its mean free path \(\frac{1}{\Sigma}\) .

With \(N\) the nuclear density:

$$\sigma \times N = \Sigma$$ $$\Sigma \times \text{neutron flux} = \text{reaction rate}$$Resonance region:

When the sum of the kinetic energy of the neutron and the binding energy correspond to an energy level of the compound nucleus, the neutron cross section exhibits a spike in its probability of interaction which are called resonances.

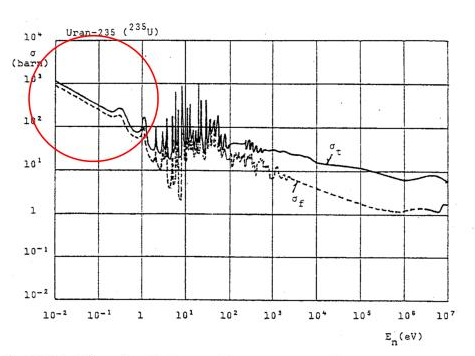

Fission cross-section for U-235:

Neutrons generated by fission are in the higher energy range, the red circle marks the thermal energy range. U-235 fissions with neutrons at all energy levels (while U-238 requires neutrons of at least 1 MeV), however in the range of 1-100 eV there are also strong resonance regions for neutron capture. So in order to keep a fission chain reaction going with U-235, neutrons need to be slowed down into the thermal region (~0.025 eV), quickly in order to avoid spending too much time in the resonance regions for capture.

In calculation, neutron energy is often simplified by splitting the energy range into two groups (thermal and fast) and taking the average in each group.